A small oasis within the death camp: The story of Alfred (Fredy) Hirsch

Alfred (Fredy) Hirsch

"Until the last child leaves, I won't"[1]

Alfred (Fredy) Hirsch was born in February 1916 in Aachen, Germany. At the age of ten his father passed away and his mother, Olga, remarried.[2] Fredy and his older brother, Paul, were active in the leadership of the German Jewish Scouting Movement (Jüdischer Pfadfinderbund Deutschland), closely related to the Maccabi Hatzair sporting organization.[3] Fredy loved sports and became a remarkable athlete; he was nominated for participation in the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games, but this dream was taken from him on account of his Jewish identity.[4] After Hitler came to power in 1933, his family immigrated to Bolivia, but Fredy chose to stay in Germany, insisting that if he ever left it would be for Palestine or not at all.[5] Unfortunately, following the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, Fredy was forced to flee to Czechoslovakia, where he became active in Maccabi Hatzair and the Halutz movement.[6] Fredy dedicated his time to working with children, most notably in the field of athletics; he instructed them in sporting activities and trained young Halutzim (pioneers) for their Aliya to Eretz Israel.[7] In October 1939 Fredy assisted a group of children in crossing the border to Denmark, from where they set sail for Palestine.[8]

Fredy (right) with his mother and brother. From: Ondrichova, Lucie. Fredy Hirsch : von Aachen uber Dusseldorf und Frankfurt am Main durch Theresienstadt nach Auschwitz-Birkenau ; eine judische Biographie, 1916-1944. Konstanz: Hartung-Gorre, 2000.

Fredy’s name was tied to ‘Hagibor’ playground in Prague. Following several Nazi orders which ostracized the Jews from Czechoslovak society, the few public spaces where Jews were still allowed to dwell were yards and playgrounds. Fredy organized athletic competitions and theatre productions for the hundreds of children in that area.[9] The playground, in a Prague suburb in the vicinity of the New Jewish Cemetery where Franz Kafka is buried, quickly became a hub of youth activities, with sporting events, conversations, games and even parties.[10]

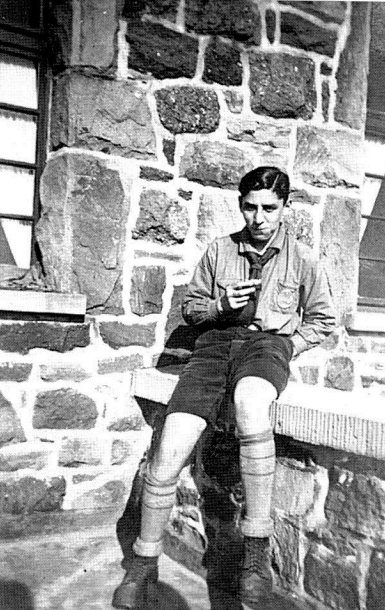

Fredy in his scouts uniform, 1931. From: Ondrichova, Lucie. Fredy Hirsch : von Aachen uber Dusseldorf und Frankfurt am Main durch Theresienstadt nach Auschwitz-Birkenau ; eine judische Biographie, 1916-1944. Konstanz: Hartung-Gorre, 2000.

In December 1941, Fredy was deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto, where he was appointed to an administrative job in the Aufbaukommando (“construction commando”). This did not prevent him from taking part in the educational activity in Theresienstadt: here, too, he organised sporting activities, and oversaw educating the youths to cleanliness and tidiness. The conditions in the ghetto were unbearable, and the care of basic cleanliness and personal hygiene could prevent death and disease.[11] Soon Fredy became a deputy of Egon (Gonda) Redlich, head of the ghetto’s youth department.[12] He insisted that the children exercise daily and practice personal hygiene, regardless of the conditions around them. He also used his knowledge of German to engage with the guards, which allowed him to secure space for a playground where, in May 1943, the Theresienstadt Maccabiah took place.[13]

One of Fredy’s mentees tells that girls used to chase Fredy around, trying to grab his attention; his friends would introduce him to the prettiest women in the ghetto, but he rejected them all. Rumor had it that he was uncapable of falling in love.[14] Another mentee of Fredy’s, Zuzana Růžičková, says:

"I think that the fact he was a homosexual bothered him. That’s why he tried to get rid of it, maybe fall in love with a girl. And his friends in Theresienstadt tried to help him. But after doing everything in his power to conquer his desires, he was proud of himself for not hiding it. Hiding it wasn’t in his character."[15]

In August 1943, 1,200 children from the recently liquidated Białystok Ghetto were transported to Theresienstadt, where they were settled in a remote part of the ghetto and isolated from its other inhabitants.[16] Rumor spread that the children refused to enter the showers out of fear that they’d be faced not with water but with gas. Despite a strict ban on any communication with them, Fredy attempted to contact their caretakers. He was caught, and in September of 1943 he was included in a transport to Auschwitz.[17]

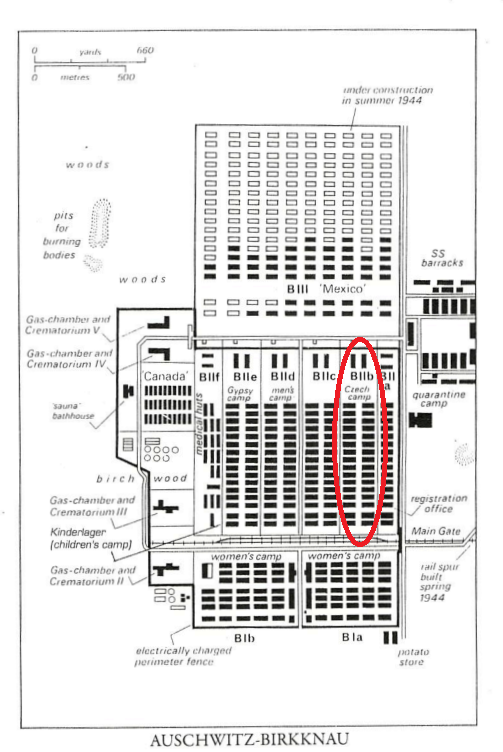

Upon arriving in Auschwitz, Fredy was sent directly to the newly built “Family Camp” (camp section BIIb) along with the rest of the Theresienstadt transport, where their hair was not shaved and they received civilian clothes.[18] The transportees were unaware that their fate was sealed that day, and that in six months’ time they were to be exterminated in the gas chambers.[19] In Auschwitz, Fredy convinced SS officers to set aside a designated Children’s Block, where once again he organised recreational activities, theatre productions, physical fitness classes and schoolrooms.[20] [21] He strictly prohibited any mention of the gas chambers and crematoria in the presence of children.[22] He aimed to maintain a small haven of happiness within the extermination camp. Zuzana says that Fredy had a boyfriend in the camp, whom everyone called 'Romeo.' Fredy and Romeo would spend most of their time together and were a known couple in the camp. She further tells that everyone respected them and that she saw that they shared a great love.[23]

Camp map of Auschwitz-Birkenau, with Biib circled in red. From: Nieuwsma, Milton J., ed. Surviving Auschwitz : Children of the Shoah 75th Anniversary Commemorative Edition / Milton J. Nieuwsma. 75th anniversary commemorative edition. Shelter Island, NY: Ibooks, 1998.

Fredy was appointed Kapo, responsible of the 'Family Camp.' As such, he was forced to assist the Germans in maintaining the order, often by inflicting brutal punishments, which went against his good nature. He used his short time in his position to transfer the prisoners who struggled with the hard labor to work with children.[24] The children received classes in an array of subjects, in secret, in small groups divided by age. In 1944, they put on a production of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs; different testimonies relay that even SS personnel watched the show, with Dr. Mengale himself cheering for the kids.[25]

In early March of that year, the September transportees were directed to prepare for relocation to another camp. None suspected deception. Rudolf Vrba, part of the Auschwitz Resistance Movement, saw Fredy’s potential as a leader to the group and asked him to head the planned rebellion.[26] Following this request, Fredy faced a dilemma: while an uprising would doubtlessly bring about the death of several SS officers, it would also sentence all the children in the camp to a certain death, even those who could potentially be saved. Fredy asked for some time to think, but the very next day Vrba confirmed that the entire transport was headed to the gas chambers. Fredy asked for one hour to meditate on the subject. When Vrba returned, he found him unconscious.[27]

The circumstances surrounding Fredy’s death remain ambiguous to this day. A doctor stated that it was a result of an overdose of tranquilizers, but it is unclear where he might have acquired a sufficient amount of pills. Some claim he was poisoned; others believe he committed suicide; some even suspect the camp doctors administered an overdose to prevent him from participating in an uprising that would risk their lives.

That same evening, March 8, 1944, the entirety of the September transport was sent to the gas chambers.[28]

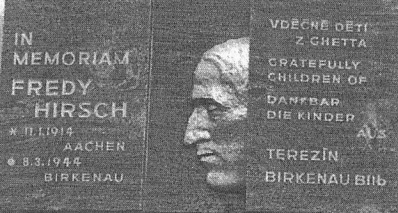

In 1996, a plaque was mounted on a wall of the old school building in Theresienstadt, bearing Fredy Hirsch’s face, carved in stone. The dedication reads: 'In Memoriam, Fredy Hirsch. Gratefully, the children of Theresienstadt, Birkenau BIIb.'[29]

Memorial plaque for Fredy Hirsch at Theresienstadt. From: Ondrichova, Lucie. Fredy Hirsch : von Aachen uber Dusseldorf und Frankfurt am Main durch Theresienstadt nach Auschwitz-Birkenau ; eine judische Biographie, 1916-1944. Konstanz: Hartung-Gorre, 2000.

[10] אביהו, רונן וכוכבי יהויקים, גוף שלישי יחיד: ביוגרפיות של חברי תנועות נוער בתקופת השואה (תל אביב: מורשת, 1994), 289.

[11] אביהו ויהויקים, 291.

[15] https://www.kan.org.il/content/kan/kan-11/p-336224/85838/ (36:00-36:40).

[17] אביהו ויהויקים, גוף שלישי יחיד, 293.

[19] אביהו ויהויקים, גוף שלישי יחיד, 294.

[23] https://www.kan.org.il/content/kan/kan-11/p-336224/85838/ (55:11-55:57).

[24] אביהו ויהויקים, גוף שלישי יחיד, 294.

[26] אביהו ויהויקים, גוף שלישי יחיד, 296-297.